The message came by email from one of my rough gemstone suppliers in South Africa. "How would you like to be able to tell your grandchildren you cut stones for Queen Elizabeth?"

That was how he began the transmission, and it got my attention. I had been dealing with this particular rough gemstone agent since 1990, and he had always been "true blue". In the gem trade, those who prove they can't be trusted are relegated to the shredder. To lose trust is to lose your place in the trading. Such a person simply disappears from the screen. This man had always been honest, and his goods were "primo". I talked about it with my wife, and we immediately replied and were directed to Mr. Michael HIng, who put me on the list of people who were interested.

The project was being coordinated to commemorate the Queen's Golden Jubilee, and therefore would be called the Jubilee Project. At first, the story we heard was that they were going to make a necklace out of the stones, but then we were told that it was to be matched pairs of stones. The coordinator would match an experienced facetor with an inexperienced one, and each would produce one stone with the understanding that the one with less experience would lean on the other for guidance. Since I'm not not in touch with any other facetor, I would just go it alone and produce the two stones.

The stone chosen for the project was Citrine, a yellow variety of Quartz. They would be provided by our South African agent. The stones would come from a deposit on the Jos Plateau in Nigeria. After each facetor registered to be a contributor, they were to purchase their citrines from our supplier.

What stones they were! The best Citrine I've ever seen. Water-clear with a color like marigolds. Deep orangey-gold. They had once been Amethyst, but had been heat-treated to turn them into Citrine. They were so nice that I ordered three extras to use for other cuts. The stones averaged between 20 to 16 carats in rough form.

We were directed to a website for the pattern we were to use, a square cushion cut called the "Classic I" invented by Jeff Graham. We downloaded the design with all the specific numbers detailing angles and settings to which our faceting machine had to be set to accomplish it.

The next step was what we call preforming, which is grinding the two stones to roughly the same size and shape. Then, one takes the stone that looks as though it would be the smallest, and cuts it while trying for the best recovery he can get. (If a facetor gets 25% recovery, he considers it nothing to be ashamed of. I average between 40% and 30%, and my best was just under 53%).

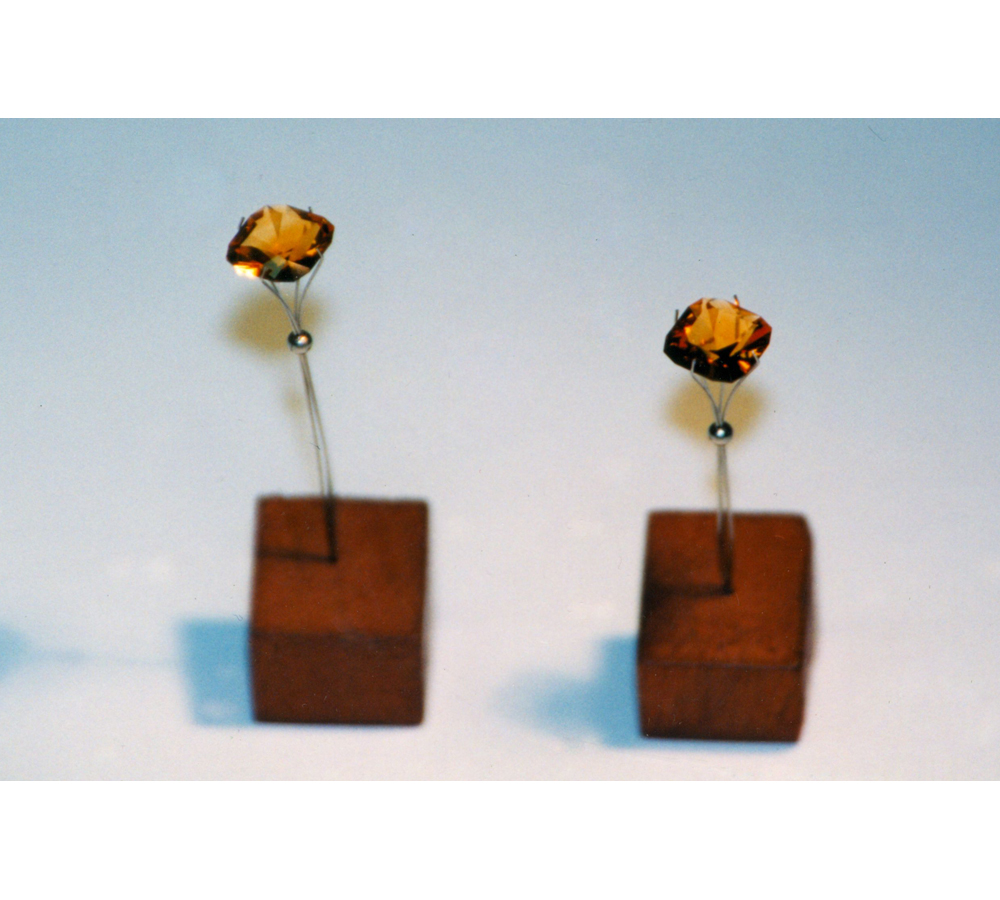

I followed each step carefully, and normally that is enough. With this particular design, the slightest discrepancies made huge differences. The upshot of this was that I had to do an entire recalibration and fine tuning of my machine. When it was done, I came up with an 11.5 X 11.5 millimeter stone of fine, deep gold. I was quite surprised to find that in cut form, the stone lost its orange overtone.

The next stone took longer because I was now cutting down to the smaller size. When it was completed, there was very little variation in the weight of the two stones, and they were a magnificent sight together.

Meanwhile, because of the "gifting" scandal at the time, Her Majesty was being pretty careful about accepting gifts. Word came from her spokesman that she would prefer the stones to be donated to a museum.

Michael Hing contacted a friend in the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., and they agreed to accept them. We were given an address to send the stones to, marked the package "Jubilee Project", and sent it off. The Smithsonian later emailed, asking about the origin of the stones, so we replied, and that was that.